Amid the alarming images of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine over the past few days, millions of people have also seen misleading, manipulated or false information about the conflict on social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, TikTok and Telegram.

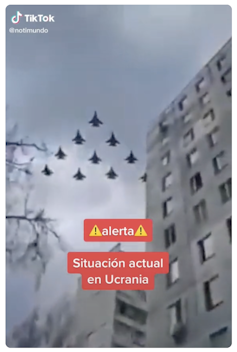

One example is this video of military jets posted to TikTok, which is historical footage but captioned as live video of the situation in Ukraine.

Old footage, rebadged on TikTok as the latest from Ukraine. TikTok Source: The Conversation

Disinformation campaigns aim to distract, confuse, manipulate and sow division, discord, and uncertainty in the community. This is a common strategy for highly polarised nations where socioeconomic inequalities, disenfranchisement and propaganda are prevalent.

How is this fake content created and spread, what’s being done to debunk it, and how can you ensure you don’t fall for it yourself?

What are the most common fakery techniques?

Using an existing photo or video and claiming it came from a different time or place is one of the most common forms of misinformation in this context. This requires no special software or technical skills – just a willingness to upload an old video of a missile attack or other arresting image, and describe it as new footage.

Another low-tech option is to stage or pose actions or events and present them as reality. This was the case with destroyed vehicles that Russia claimed were bombed by Ukraine.

Using a particular lens or vantage point can also change how the scene looks and can be used to deceive. A tight shot of people, for example, can make it hard to gauge how many were in a crowd, compared with an aerial shot.

Taking things further still, Photoshop or equivalent software can be used to add or remove people or objects from a scene, or to crop elements out from a photograph. An example of object addition is the below photograph, which purports to show construction machinery outside a kindergarten in eastern Ukraine.

The satirical text accompanying the image jokes about the “calibre of the construction machinery” - the author suggesting that reports of damage to buildings from military ordinance are exaggerated or untrue.

Close inspection reveals this image was digitally altered to include the machinery. This tweet could be seen as an attempt to downplay the extent of damage resulting from a Russian-backed missile attack, and in a wider context to create confusion and doubt as to veracity of other images emerging from the conflict zone.

What’s being done about it?

European organisations such as have begun compiling lists of dubious social media claims about the Russia-Ukraine conflict and debunking them where necessary.

Journalists and fact-checkers are also working to verify content and raise awareness of known fakes. Large, well-resourced news outlets such as the BBC are also calling out misinformation.

Social media platforms have added new to identify state-run media organisations or provide more background information about sources or people in your networks who have also shared a particular story.

They have also tweaked their algorithms to change what content is amplified and have hired staff to spot and flag misleading content. Platforms are also doing some work behind the scenes to detect and information on state-linked information operations.

What can I do about it?

You can attempt to fact-check images for yourself rather than taking them at face value. An we wrote late last year for the Australian Associated Press explains the fact-checking process at each stage: image creation, editing and distribution.

Here are five simple steps you can take:

1. Examine the metadata

This claims Polish-speaking saboteurs attacked a sewage facility in an attempt to place a tank of chlorine for a “false flag” attack.

But the video’s metadata – the details about how and when the video was created – it was filmed days before the alleged date of the incident.

To check metadata for yourself, you can download the file and use software such as Adobe Photoshop or Bridge to examine it. Online also exist that allow you to check by using the image’s web link.

One hurdle to this approach is that social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter often strip the metadata from photos and videos when they are uploaded to their sites. In these cases, you can try requesting the original file or consulting fact-checking websites to see whether they have already verified or debunked the footage in question.

2. Consult a fact-checking resource

Organisations such as the , , and maintain lists of fact-checks their teams have performed.

The AFP has already a video claiming to show an explosion from the current conflict in Ukraine as being from the 2020 port disaster in Beirut.

3. Search more broadly

If old content has been recycled and repurposed, you may be able to find the same footage used elsewhere. You can use or to “reverse image search” a picture and see where else it appears online.

But be aware that simple edits such as reversing the left-right orientation of an image can fool search engines and make them think the flipped image is new.

4. Look for inconsistencies

Does the purported time of day match the direction of light you would expect at that time, for example? Do or clocks visible in the image correspond to the alleged timeline claimed?

You can also compare other data points, such as politicians’ schedules or verified sightings, vision or imagery, to try and triangulate claims and see whether the details are consistent.

5. Ask yourself some simple questions

Do you know where, when and why the photo or video was made? Do you know who made it, and whether what you’re looking at is the original version?

Using online tools such as or can potentially help answer some of these questions. Or you might like to refer to this list of you can use to “interrogate” social media footage with the right level of healthy scepticism.

Ultimately, if you’re in doubt, don’t share or repeat claims that haven’t been published by a reputable source such as an international news organisation. And consider using some of these when deciding which sources to trust.

By doing this, you can help limit the influence of misinformation, and help clarify the true situation in Ukraine.

T.J. Thomson is a senior lecturer in visual communication and media at Queensland University of Technology. He has received funding from the AAP, the Australian Academy of the Humanities, and from the Australian Research Council through Discovery Project DP210100859. He is also a past contributor to the Australian Associated Press.

Daniel Angus is a professor of digital communication at Queensland University of Technology. He receives funding from Australian Research Council through Discovery Projects DP200100519 ‘Using machine vision to explore Instagram’s everyday promotional cultures’, DP200101317 ‘Evaluating the Challenge of ‘Fake News’ and Other Malinformation’, and Linkage Project LP190101051 'Young Australians and the Promotion of Alcohol on Social Media'.

Paula Dootson is a senior lecturer at Queensland University of Technology. She has received funding from the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Queensland Government, and Natural Hazards Research Australia.