Four years after former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull announced a major shake-up of intelligence and espionage laws to limit the impact of foreign interference on the Australian political system, the issue is once again dominating the headlines.

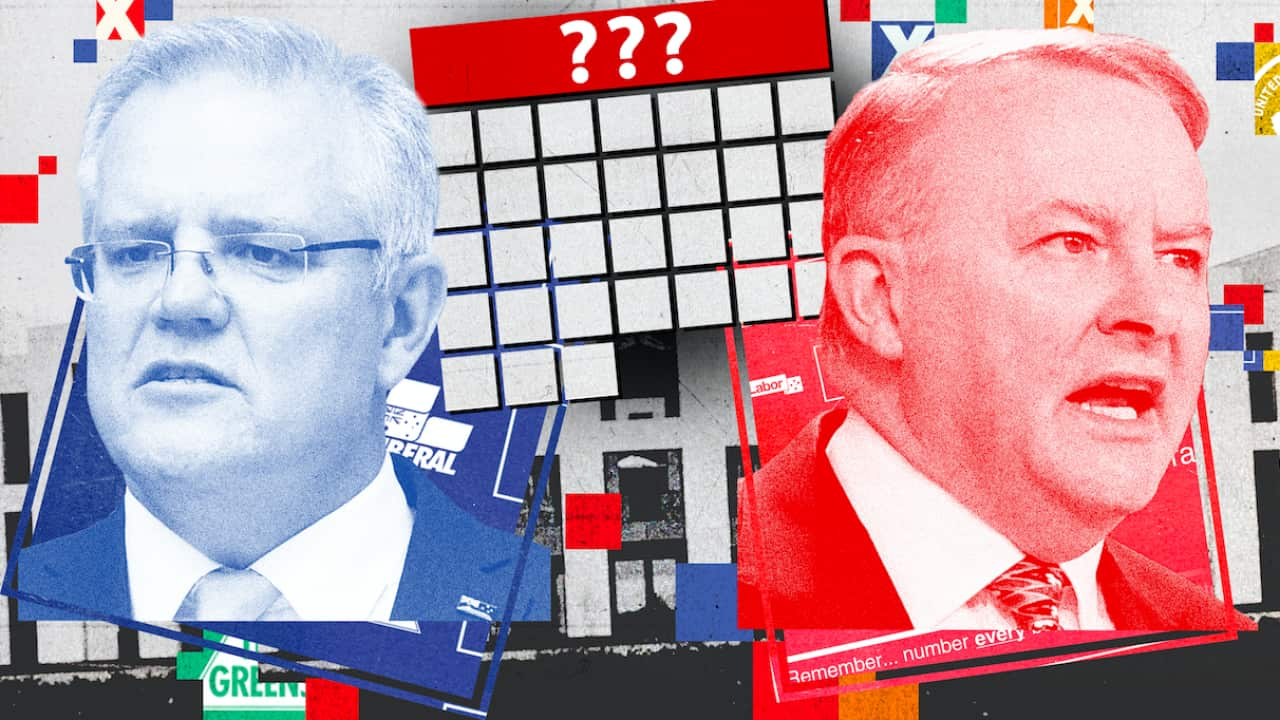

Dramatic scenes unfolded in federal parliament this week when Prime Minister Scott Morrison labelled deputy Labor leader Richard Marles a “Manchurian candidate”. The term is based on the book and movie of the same name and used to describe a person, especially a politician, who’s used as a puppet by a foreign power.

While Mr Morisson has withdrawn his comments, Mike Burgess – director-general of the country’s top spy agency, Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) – referred to the politicisation of national security issues as “not helpful” in a rare TV interview with the ABC on Wednesday.

But what exactly is foreign interference? What are the tools of foreign interference? Who are the biggest threats and the most vulnerable targets? And can foreign interference really have an impact on Australia’s upcoming federal election?

Here are your questions answered:

What is foreign interference?

“Foreign interference means attempts by foreign governments to influence through covert means the democratic political processes and outcomes in other countries,” Dennis Richardson, former chief of ASIO, told SBS News.

China and Russia are the two biggest threats when it comes to foreign interference, while democracies such as the United States of America, the United Kingdom and Australia are the biggest targets, he said. “But non-democratic countries can be a target, too. Russia and China would have an interest in influencing some countries in Africa, some countries in the Middle East and some countries on their own borders."

“But non-democratic countries can be a target, too. Russia and China would have an interest in influencing some countries in Africa, some countries in the Middle East and some countries on their own borders."

Dennis Richardson, former chief of ASIO. Source: AAP

The objective of foreign interference is – first and foremost – to create confusion, uncertainty and division.

“Occasionally, foreign interference aims to influence outcomes within political parties or within parliaments, and to influence the direction of debate within a democratic country by using the openness of democracies against the system itself,” Mr Richardson said.

He said attempts to influence the outcome of the vote on Brexit in the UK and interfere with the 2016 presidential elections in the US are two of the most stark examples of foreign interference.

Tools of foreign interference

Large donations to political parties and well-orchestrated misinformation campaigns are just some of the tools some countries may use to interfere with the political systems of other nations.

Fergus Hanson – director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s (ASPI) International Cyber Policy Centre – told SBS News the use of money can be very effective.

“There have been instances when large donations made by wealthy individuals have resulted in a politician changing their approach on a particular foreign policy issue,” Mr Hanson said. “We also see in the information environment where information operations are run by foreign states. We see countries like Russia and China trying to shape narratives through fake [digital] accounts and artificially manipulate information environments to create disinformation in particular countries.

“We also see in the information environment where information operations are run by foreign states. We see countries like Russia and China trying to shape narratives through fake [digital] accounts and artificially manipulate information environments to create disinformation in particular countries.

Fergus Hanson is the director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s (ASPI) International Cyber Policy Centre. Source: Supplied

Five Australian universities have just filed a joint report, , which highlights the widespread use of digital misinformation campaigns.

According to the report, Russia’s state-sponsored Internet Research Agency actively uses social media platforms such as Facebook and employs up to 1,000 staff that operate in a “well-resourced”, “well-coordinated”, “24/7” environment to perpetuate misinformation within other countries that can support Russian aims.

Stark examples of foreign interference

ASIO says it recently detected and disrupted a foreign interference plot in the lead-up to an election in Australia.

“Australians who were targeted by the foreign intelligence service included current and former high-ranking government officials, academics, members of think tanks, business executives and members of a diaspora community," Mr Burgess said as part of ASIO’s annual threat assessment, delivered in Canberra on 9 February.

While Mr Burgess declined to reveal which state or territory the act of foreign interference related to, he said the case involved a wealthy person – described as the “puppeteer” – who had “direct and deep connections with a foreign government and its intelligence agencies”.

“The puppeteer hired a person to enable foreign interference operations and used an offshore bank account to provide hundreds of thousands of dollars for operating expenses,” Mr Burgess said.

"The employee hired by the puppeteer began identifying candidates likely to run in the election who either supported the interests of the foreign government or who were assessed as vulnerable to inducements and cultivation.

“The puppeteer and the employee plotted ways of advancing the candidates’ political prospects through generous support, placing favourable stories in foreign language news platforms and providing other forms of assistance.

“Our intervention ensured the plan was not executed, and harm was avoided."

The candidates had no knowledge of the plot.

Can foreign interference influence Australian politics?

Yes and no, said the ASPI's Mr Hanson.

“If you’re talking about foreign interference being used to get a candidate, who’s been planted by a foreign state, elected, then yes, absolutely, I think that could happen,” he said.

“But could it change the federal election from being the Labor party elected to being the Liberal party elected or vice versa? I think that’s probably pretty unlikely."

Mr Richardson agrees.

“The democratic institutions and processes in Australia are [far stronger than countries such as the US] and I think the capacity of foreign players to significantly influence [the result of federal election] is limited,” he said.

What makes Australia less vulnerable than the US?

A paper-based voting system as opposed to online voting (offered in a number of states in the US) is the key factor that differentiates the federal election processes in Australia from the US, making the Australian structure far safer and more rigorous.

“At some point the system becomes digitised [in Australia] about how many people voted for which candidate in different electorates, so there’s potential to digitally manipulate the final tally,” Mr Hanson said.

“But our paper-based system is quite difficult to interfere with [in the initial stages of the voting],” he said.

Compulsory voting also makes it harder for foreign players to interfere too much with the Australian political system, he said.

“If you take countries like the United States where there’s voluntary voting, the way the two main parties mobilise the groups to come out and vote is by taking strong positions on either the left or the right. People get exercised about that and want to go out and vote.

“Whereas in a compulsory system where everyone has to vote, both parties have to gravitate towards the centre because that’s where the biggest voting block exists.

“There are differences around the edges between Labor and Liberal, but they tend to take a lot of common positions to make sure they attract that central voter base.

“And because of that it’s much harder for foreign agents to whip up a storm or to leverage those extremist views to manipulate and interfere with elections."

Additional reporting by AAP.