As a senior official in Australia’s Immigration Department in the late 1990s, I frequently met counterparts in Europe and North America who were exasperated by their inability to make headway against the exploitation and abuse of hundreds of thousands of migrant farm workers.

They also worried about the infiltration of criminal gangs who controlled how the migrant workers were allocated to farmers, profiting from that control.

I walked away from those conversations smug in the view Australia would never introduce a dedicated farm worker visa like the United States .

Fast forward two decades, and not only are we about to have an Agriculture Visa, we also have unsuccessful asylum seekers trafficked to work on Australian farms.

Work without protection

There are currently about 95,000 asylum seekers in Australia, about 30,000 of whom have had asylum refused at both the initial and by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal stage and are not legally able to work.

Many work on farms, including those not legally able to.

A retired teacher in Mildura recently contacted me to talk about how appallingly they are being treated and how they live in the shadows to avoid the authorities.

They can never complain about their treatment and have to accept whatever work they can get under whatever conditions as those who have been refused asylum have no legal right to work.

Last year, at the encouragement of farm lobby groups, Agriculture Minister David Littleproud spoke cautiously in favour of an amnesty for undocumented migrants (mainly unsuccessful asylum seekers) working on farms.

It would have given them rights and help protect them from exploitation.

The idea was near- instantly rejected by Attorney General Michaelia Cash, without an offer of an alternative solution.

Amnesty rejected

As in North America and Europe, Australia seems to want to sweep the problems of undocumented migrant farm workers under the carpet.

Compounding this exploitation, we have for more than ten years steadily expanded Australia’s for seasonal farm workers and “streamlined” their provisions for the convenience of employers and labour hire companies.

At least 30 people have died on these visas while in Australia.

The government dismisses this as bad luck, a normal death rate. That’s unlikely. If working holiday makers or students had been dying at such a rate, there would have been more than 1,000 working holiday maker deaths in the last 10 years and more than 1,400 student deaths.

Absconding workers

In the last 12 months, more than 1,000 Pacific Island visa holders have “absconded” from their employers in the face of exploitation and abuse.

Earlier this month a number of Pacific Island farm workers gave evidence to a Senate committee inquiring into the treatment of migrant farm workers.

They showed pay slips with extraordinary deductions for a host of “innovative” reasons that left the workers with not nearly enough money to buy food let alone support their families back home.

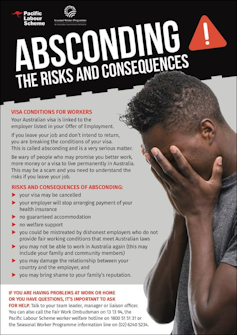

And how did the government respond? It issued warnings to these workers not to abscond. It is threatening the workers who gave evidence with deportation.

How the government thinks that will solve anything is a mystery.

The government in 2019 promised legislation to address exploitation in response to recommendations of its own .

Posters, instead of support. Source: The Conversation

Even if the legislation did proceed, the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) would not have enough resources to enforce it. The FWO is drowning in its current workload.

Experience overseas shows that even strong and well resourced regulations have failed to make much impact on the exploitation of migrant farm workers.

A new Agricultural Visa

In the second half of 2021, the government announced a new “” for people from nearby Asian countries.

Littleproud described this visa as a landmark reform to Australia’s agriculture industry while Foreign Minister Marise Payne said it would build on the strong performance of the Pacific Island seasonal worker visas.

Both ministers seem to think Australia can somehow avoid the near slavery-like conditions experienced for decades by migrant farm workers elsewhere by eventually giving these workers (but not the Pacific Island workers) a pathway to permanent migration.

They could not be more wrong. The lure of eventual permanent migration will make these workers, most of whom have very little English and few post-secondary skills, even more vulnerable to exploitation.

Employers and labour hire companies will know these workers cannot complain lest this close off the pathway to residence.

A less egalitarian Australia

It is not surprising the Department of Home Affairs is struggling to identify how this pathway will work, while the countries with which Australia is trying to reach an agreement are reluctant reluctant to sign up to putting their citizens in a vulnerable position.

Even more important is that these visas entrench the view there are some jobs Australians won’t do, fundamentally changing the nature of Australian society.

Once accepted, industry will press for an ever-widening range of low skill and low pay jobs to have their own dedicated visa – meat workers, cleaners, shelf stackers, housekeepers in hotels, the list is endless.

Rather than sleep-walking into this change to Australian society, shouldn’t we be debating this ahead of the election?

Abul Rizvi is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne

He was a senior official in the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007 when he left as Deputy Secretary. He has recently published a book titled Population Shock.