If you can get your hands on a telescope, there are few sights more spectacular than the magnificent ringed planet – Saturn.

Currently, Saturn is clearly visible in the evening sky, at its highest just after sunset. It’s the ideal time to use a telescope or binoculars to get a good view of the Solar System’s sixth planet and its famous rings.

But in the past few days, a slew of articles have run like wildfire through social media. Saturn’s rings, those articles claim, are rapidly disappearing – and will be gone by 2025!

So what’s the story? Could the next couple of months, before Saturn drops out of view in the evening sky, really be our last chance to see its mighty rings?

The short answer is no. Whilst it’s true the rings will become almost invisible from Earth in 2025, this is neither a surprise nor reason to panic. The rings will “reappear” soon thereafter. Here’s why.

Tipping and tilting Earth

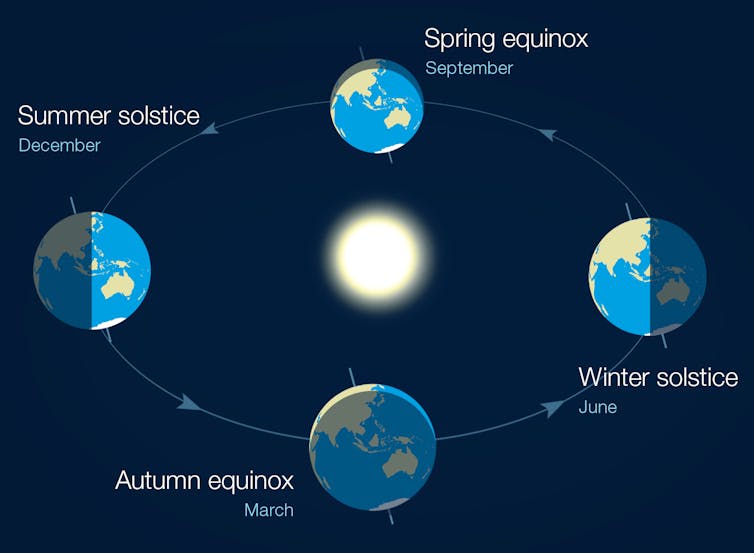

To understand why our view of Saturn changes, let’s begin by considering Earth on its constant journey around the Sun. That journey takes us through the seasons – from winter to spring, summer and autumn, then back again.

What causes the seasons? Put simply, Earth is tilted towards one side, as seen from the Sun. Our equator is tilted by about 23.5 degrees from the plane of our orbit.

Earth has seasons because its axis is tilted. The axis always points in the same direction as our planet orbits the Sun. Source: The Conversation / Bureau of Meteorology

From the Sun’s viewpoint, Earth appears to “nod” up and down, alternately showing off its hemispheres as it moves around our star. Now, let’s move on to Saturn.

Saturn, a giant tilted world

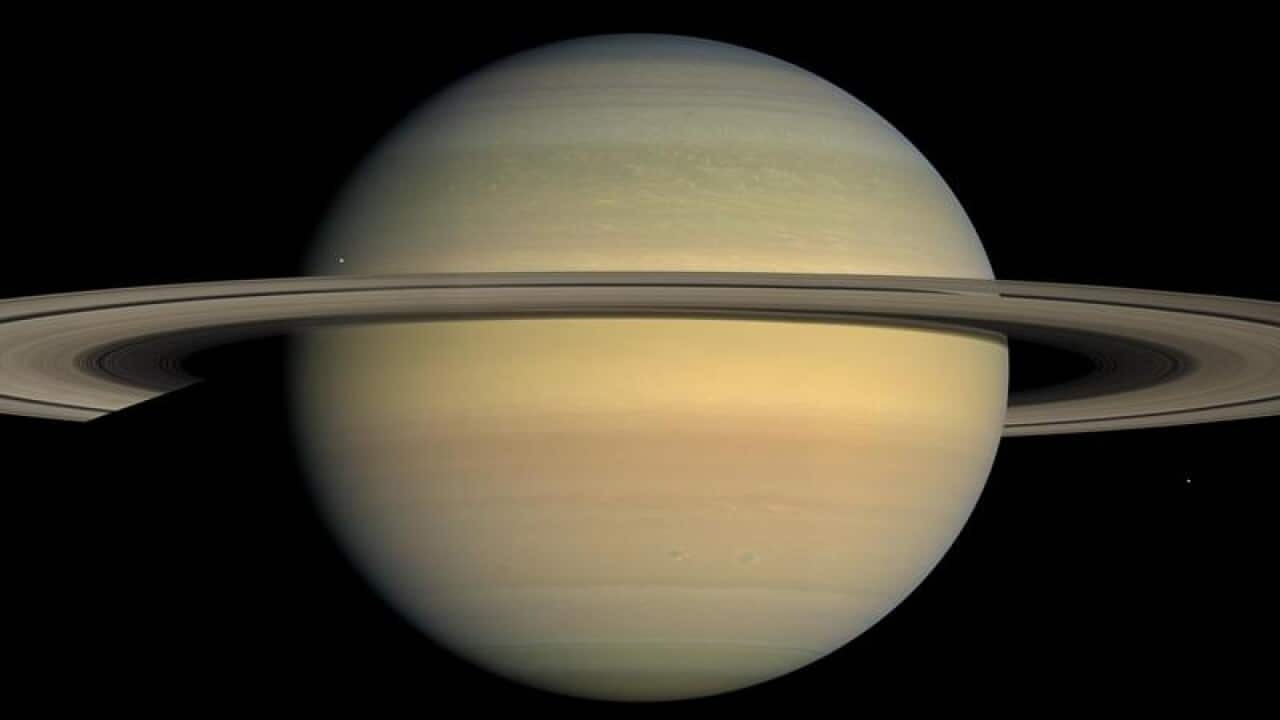

Just like Earth, Saturn experiences seasons, but more than 29 times longer than ours. Where Earth’s equator is tilted by 23.5 degrees, Saturn’s equator has a 26.7 degree tilt. The result? As Saturn moves through its 29.4-year orbit around our star, it also appears to nod up and down as seen from both Earth and the Sun.

What about Saturn’s rings? The planet’s enormous ring system, comprised of bits of ice, dust and rocks, spreads out over a huge distance – just over 280,000km from the planet. But it’s very thin – in most places, just tens of metres thick. The rings orbit directly above Saturn’s equator and so they too are tilted to the plane of Saturn’s orbit.

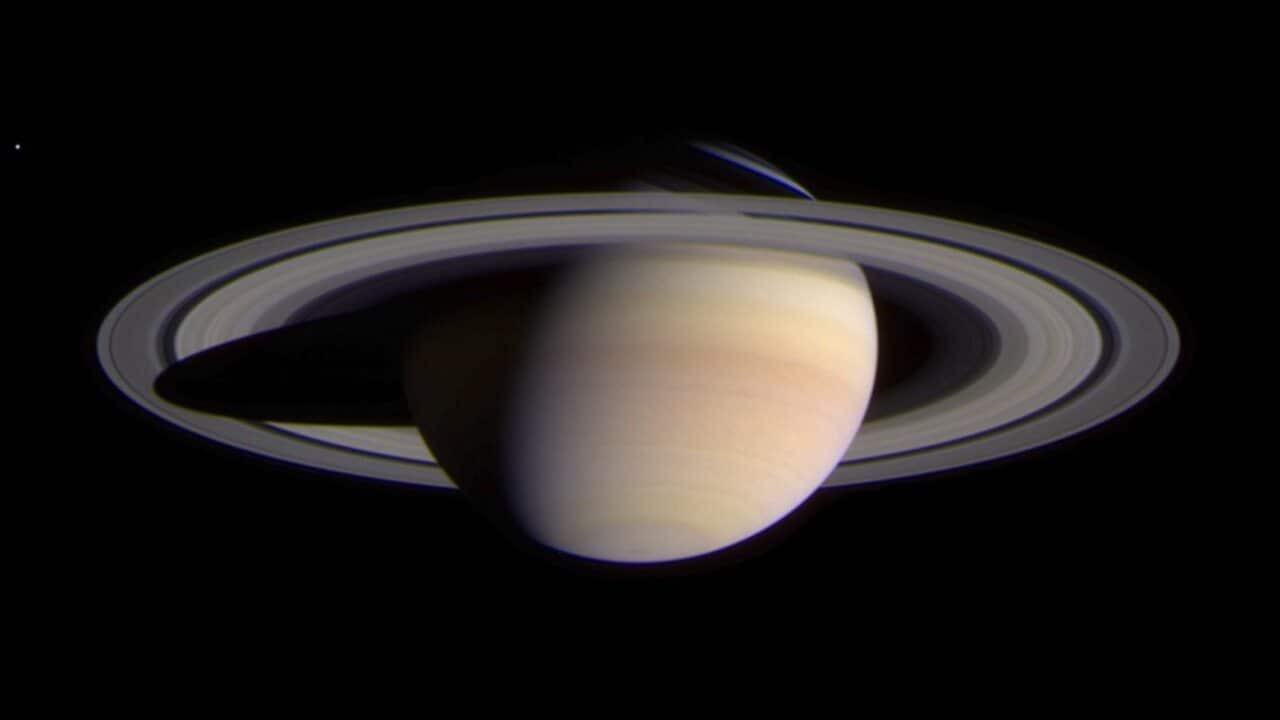

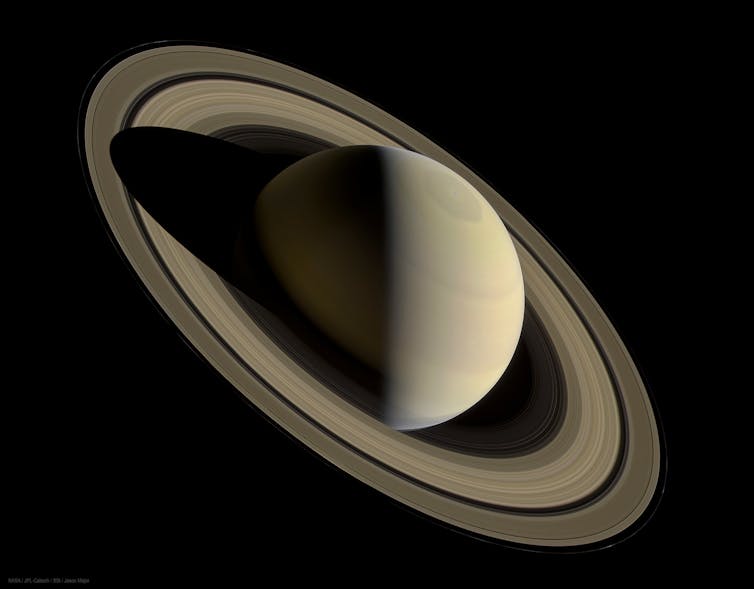

A mosaic of images from NASA’s Cassini mission taken in 2016, highlighting Saturn’s axial tilt during its northern hemisphere summer. Source: The Conversation / NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI. Composite by Jason Major via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

So why do Saturn’s rings ‘disappear’?

The rings are so thin that, seen from a distance, they appear to vanish when edge on. You can visualise this easily by grabbing a sheet of paper, and rotating it until it is edge on – the paper almost vanishes from view.

As Saturn moves around the Sun, our viewpoint changes. For half of the orbit, its northern hemisphere is tilted towards us and the northern face of the planet’s rings is tipped our way.

When Saturn is on the other side of the Sun, its southern hemisphere is pointed our way. For the same reason, we see the southern face of the planet’s rings tilted our way.

The best way to illustrate this is to get your sheet of paper, and hold it horizontally – parallel to the ground – at eye level. Now, move the paper down towards the ground a few inches. What do you see?

The upper side of the paper comes into view. Move the paper back up, through your eye line, to hold it above you and you can see the underside of the paper. But as it passes through eye level, the paper will all but disappear.

A simulation demonstrating the 29.5-year orbital period of Saturn, as viewed from Earth. The ring system lies directly above Saturn’s equator, so both sides of its disk are visible from Earth during the course of one Saturnian year. Source: The Conversation / Tdadamemd / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Twice per Saturnian year, we see the rings edge on and they all but vanish from view.

That’s what’s happening in 2025 – the reason Saturn’s rings will seemingly “disappear” is because we will be looking at them edge on.

This happens regularly. The last time was in 2009 and the rings gradually became visible again, over the course of a few months. The rings will be edge on once again in March 2025. Then they’ll gradually come back into view as seen through large telescopes, before sliding out of view again in November 2025.

Thereafter, the rings will gradually get more and more obvious, reappearing first to the largest telescopes over the months that follow. Nothing to worry about.

If you want to clearly see Saturn's rings, now is your best chance, at least until 2027 or 2028!

Jonti Horner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.