Key Points

- In the 1970s, distinctive silverware was retrieved from the Batavia shipwreck.

- Australian historians studying the silverware believe the items were luxurious goods intended for the Mughal Empire in India.

- The Batavia is infamous for the atrocities committed by the survivors on each other in their time stranded on a remote island.

- The items excavated from the shipwreck and now exhibited in the WA Museum include elaborate silver jars, large dishes, bowls and bedposts.

The ship named Batavia, with over 340 passengers aboard, met its demise in the Houtman Abrolhos islands off the coast of Western Australia in 1629.

However, in the year that followed living on a tiny island, now called Beacon Island, one group turned on another and massacred an estimated 120 men, women, and children.

The perpetrators were eventually brought to justice with some tortured and hanged on nearby Seal Island and others killed on the way to Batavia, now known as Jakarta, in modern-day Indonesia.

In the 1970s, a team of maritime archaeologists from the Western Australian Museum excavated the wreck, uncovering artefacts including silverware.

These items, now part of the museum's collection, were among the cargo destined for export to India.

Divers excavating more artefacts from the wreck of the Batavia in 2016. Credit: AAP Image/Western Australian Museum, Jeremy Green

The Mughals held sway over the Indian subcontinent from the early 16th century until the mid-19th century.

The Dutch East India Company was established in 1602 with the aim of dominating the lucrative spice trade and expanding Dutch commercial interests in Asia.

Jeremy Green, a curator at the WA Museum, examined these artefacts in 1989, marking the first association with trade in India.

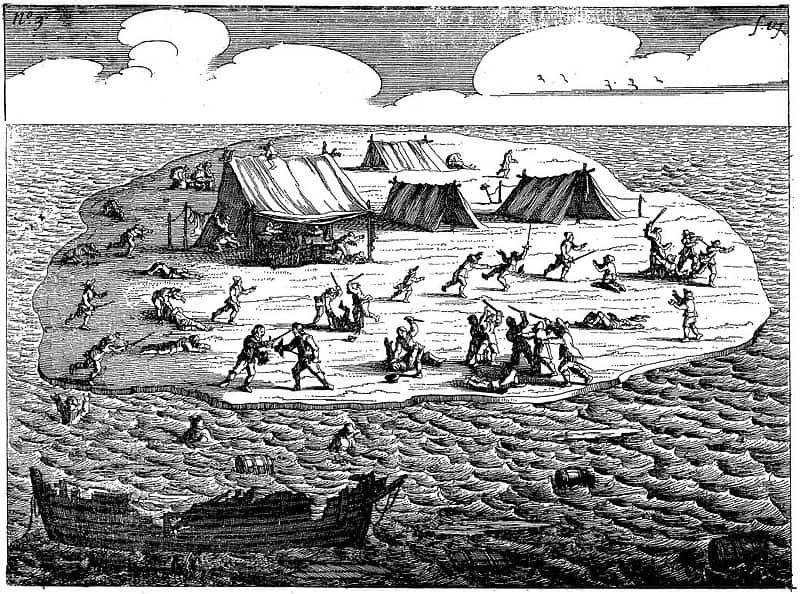

Plate 3 from the 1647 Dutch book, "Unlucky voyage of the ship Batavia", depicts the slaughter of innocent men, women and children by a rogue group of fellow survivors. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/The Voyage of the Batavia (Australian Maritime Series Number Two), Hordern House, 1994/Public Domain

"Our recent project in Australia has delved deeper into the engravings and depictions on these objects," Wattel explained.

"We've discovered that they specifically depict the Mughal Emperor Jahangir (the fourth Mughal Emperor whose son Shan Jahan would later go on to commission the Taj Mahal) and were tailored for his court and entourage, reaffirming the strong Indian connection of these artefacts."

The Indian connection

The items excavated from the shipwreck and now exhibited at the WA Museum include elaborate silver jars, large dishes, bowls and bedposts.

"The objects found were commissioned by the Batavia's commander, Francisco Pelsaert, who had previously been stationed in India for seven years by the Dutch East India Company and was knowledgeable about the region," Wattel said.

A water jug or ewer crafted by an unknown Dutch silversmith in 1628 and now on display in the WA Museum. Credit: Robert Erdmann

During this period, silversmiths in Amsterdam crafted several items commonly used in India, incorporating iconography.

These items were created in 1628 within the brief span of two months, he said, adding that, "It will be hard to know the value of these items today but it can be estimated at around $10 million."

Wattel said that he viewed the items as trans-cultural objects, crafted by Europeans for Indians. They are key to understanding how Europeans viewed the Mughal empire in India at that time.

One of the 122 islands which make up the Houtman Abrolhos islands about 80km off the mid-north coast of Western Australia. Source: Moment RF / Sammyvision/Getty Images

"On the water jug (ewer), Emperor Jahangir is depicted in three cartouches. While his likeness is accurate, the clothes he is wearing are purely imaginative, evoking general Eastern styles.

"For instance, the Mughal nobility typically wore very small turbans, but Jahangir is shown wearing a large turban here."

He further pointed out that the emperor was also depicted with his shoes on the carpet, a practice that would be unacceptable for the Mughals, who never wore shoes on carpets.

"The Dutch silversmiths and the commissioner aimed to create these objects for an Indian audience. However, due to their misunderstandings and misinterpretations of Indian culture, the resulting objects exhibit characteristics of both cultures, making them what I would call trans-cultural."

A silver plate created by Abraham van der Plaetsen in 1628, which is housed in the WA Museum. Credit: Robert Erdmann

Wattel said the items, which were now available to the public through a digital exhibition, had barely been studied by historians.

"So far, these items have been unknown, and I believe many Indian historians are still unaware of (their) existence," he said.

A replica of the Batavia. Source: iStockphoto / Sannie32/Getty Images

"Rather than a European interpretation of Indian culture, these items were attempts by Europeans to authentically recreate Indian cultural impressions for an Indian audience."

The items are ready to be showcased on the WA Museum's website, where visitors can view them along with the accompanying stories.