Australia’s skilled migrant visa 189 is often referred to as the “lucky visa” because its holders enjoy the full rights and privileges of a permanent resident from day one in Australia, which isn’t the case for many other types of visas.

But that reputation may be misleading, as those who come to Australia on skilled visas aren’t always lucky enough to find work in their field.

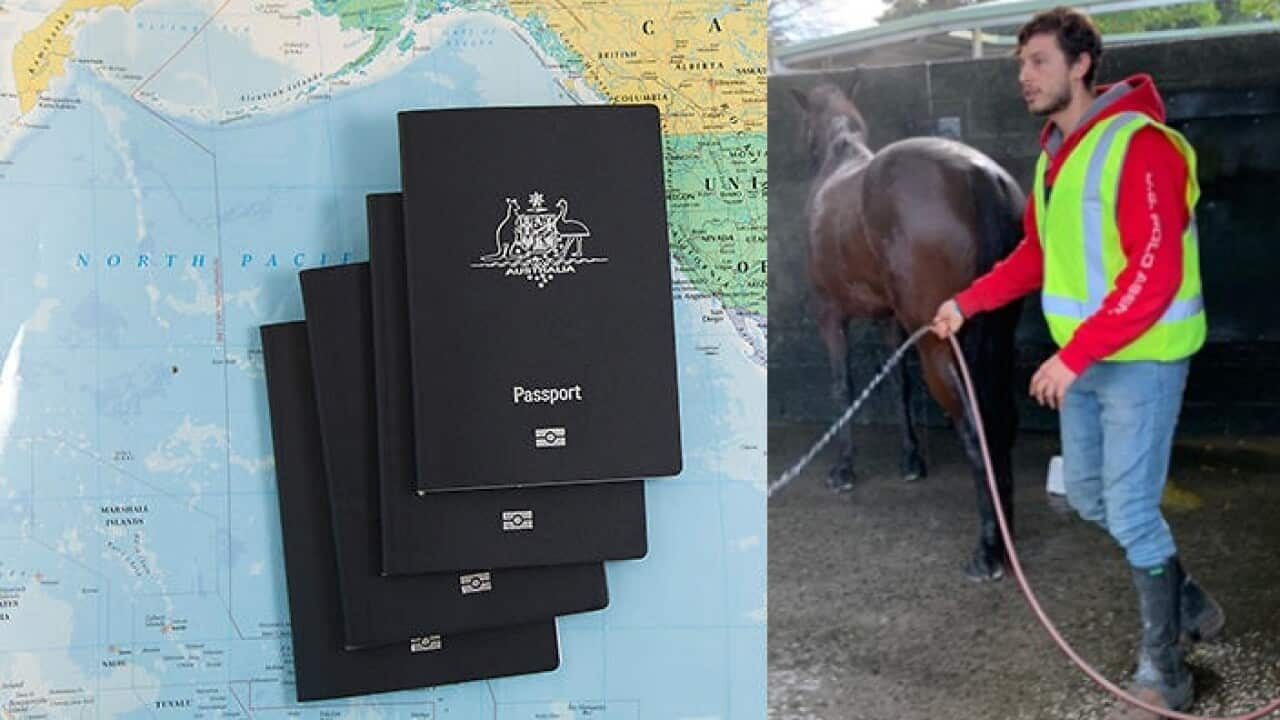

Shovelling manure with an engineering degree

Shady El-Agamy is a 28-year-old Egyptian migrant who was granted a 189 skilled migrant visa just nine months after applying from Cairo.

The professional skill for which Shady was selected is engineering, having studied petroleum engineering and later specialising as an occupational health and safety engineer with 3 years’ experience and a British certification under his belt. He believed demand for his skills must be high in Australia, but when he landed in Sydney in May of 2018, he discovered a different reality.

Not only was Shady unable to find a job in his field, but he says he never received replies from the dozens of employers and recruitment agencies he applied for work through. After a few months, his savings looked like running out.

Like many migrants, Shady realised his options were limited and looked for ‘temporary’ work to get by until he could land a job in his field. That job was shovelling manure at a horse stable, and a year later he’s still working the same job, barely making minimum wage. Shady is not an isolated case.

Shady El-Agamy Source: Instagram

The stats say…

According to a study from settlement agency AMES Australia, in 2013 only 53 per cent of skilled migrants to Australia managed to find jobs in their nominated field. Almost half ended up having to take whatever jobs they could find in order to get by.

That figure appears to have improved over the past six years. A spokesperson from Department of Home Affairs (DoHA) however tells SBS Arabic24 that:

“Almost 70 per cent of the surveyed Skilled Migrant population are employed in either their nominated occupation or an occupation of equivalent or higher skill level.”

Even with the DoHA numbers, why were skilled migrants recruited to come to Australia to work in fields said to lack skilled workers, when the job market may prove otherwise?

Why the discrepancy?

The Department of Immigration (previously Home Affairs and Immigration) sets annual skilled visa quotas and decides on the required professions. For example, this year the Department of Immigration announced it required Aeronautical Engineers, Advertising Managers and Biochemists amongst 212 occupations on its .

DoHA says, “the lists are designed to be dynamic and target skills needs in the short, medium and longer term, as well as skills needed in regional Australia”.

According to immigration lawyer Judy Hamawi, the occupations on this list are decided based on consultations between the department, state governments, economic and social organisations as well as international research.

This means that if you see your occupation on this list, the expectation is that demand exists for that job in Australia and not enough supply. Yet, this begs the question of how come 30 per cent of migrants still can’t get jobs in the fields they were nominated to come to Australia?

DoHA says there are many reasons for the discrepancy, among them being migrants choosing to change occupation when they come to Australia. Changes in personal or family circumstances, care responsibilities, health issues, financial circumstances or moving to different areas also have an impact.

Got ‘local experience’?

Many migrants face problems when trying to secure a job in the Australian job market for their lack of “local experience”, a standard pre-requisite by most Australian employers.

According to Judy, this requirement is an obstacle even Australian graduates struggle to overcome. Migrants find their certifications and qualifications invalid to Australian employers, something many are unaware of prior to immigrating.

Source: AAP

Centrelink? Come back in two years

Contrary to common belief, there is no Centrelink relief available for newly arrived skilled migrants.

According to Ms Hamawi, skilled migrants enjoy every privilege as a permanent resident including all government services, except Centrelink. generally have to wait two or four years before receiving payments and services, with some , she says, but the skilled migrant visa is not one of them.

When Shady sought help in finding a job, Centrelink turned him away.

“I told them I don’t want any money, but can you at least help me find a job in my field,” he says. “They said I can’t even be registered with them. Come back in two years.”

Is there a fix?

While Ms Hamawi confirms the government is under no obligation to assist migrants to find work after they’ve arrived in Australia, one agency is trying to change that.

Australian Management and Education Services (AMES Australia) established a program that was partially funded by the government to help newly arrived skilled migrants get jobs that fit their qualifications and experiences all while harnessing the skills and cultural knowledge migrants bring with them.

DoHA also said the government is now placing more focus on employer-sponsored places under the skilled visa stream, increasing the number of places available in 2019-20 to 39,000.

Not all bad

Despite skilled migrants’ struggles to secure jobs in their nominated professions, it’s not all bad in terms of general employment.

According to DoHA, the unemployment rate of skilled migrants is better than that of the average Australian. After 18 months of settlement, the skilled migrant unemployment rate is currently 3.5 per cent compared to 5.2 per cent for the general population.