Highlights

- The Sanioura family has been waiting for four years for the ATT to hear their case.

- They are among a backlog of 32,000 cases to be heard, which is down from more than 60,000 cases in 2020.

- AAT President David Thomas says the body is "not sufficiently resourced".

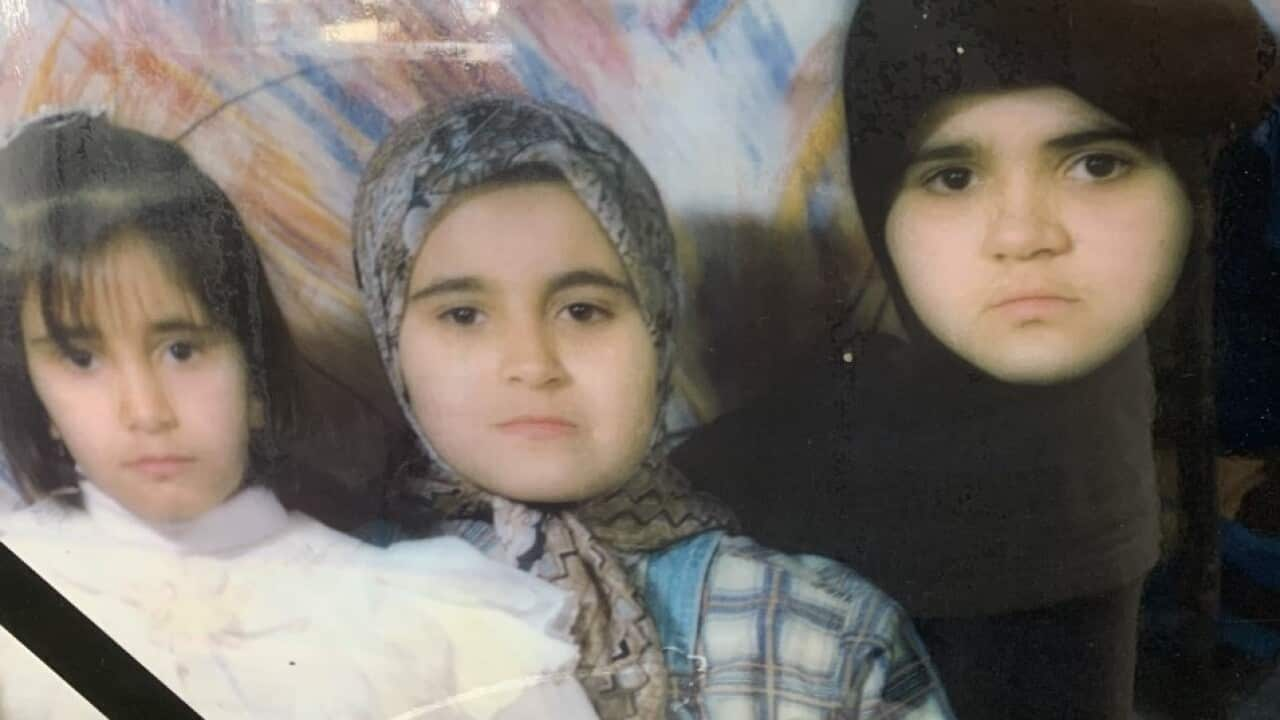

Samar Sanioura has been living in Australia on a refugee visa since 2015, hoping that she, her adult son and two daughters are able to obtain permanent residency.

The Palestinian family's first brush with Australia occurred in 2014 when Ms Sanioura's oldest daughter was awarded a scholarship to study at the Canberra Institute of Technology (CIT).

When the family arrived from Jerusalem for a visit later that year, they found in Australia a sense of security they deeply missed at home due to family problems and political instability.

“We found peace here in Australia, therefore, two months after our arrival, we decided to apply for asylum.

“We hired a lawyer and things seemed straightforward and we completed the initial procedures quickly,” she told SBS Arabic24.

“I couldn't sleep comfortably until I got to Australia.”

But despite how smoothly the first steps were for the family, the rest of the process has been anything but.

"Our application was rejected in 2017 because they didn't find the evidence we presented strong enough. They said we could go back home safely."

Ms Sanioura appealed to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) but has not received news about the review in four years.

The AAT is responsible for reviewing certain visa decisions made by the Department of Home Affairs or government ministers and is considered a crucial appeals process for migrants and refugees.

“Our hearing was supposed to take place in November this year, but they contacted our lawyer and told her that the hearing was postponed without any new date being set,” she explained.

The family’s case is not an isolated one.

In its latest annual report, the tribunal admitted that it lacked the resources to deal with a backlog of tens of thousands of immigration and refugee cases.

The backlog is . This has caused some applicants like Ms Sanioura to wait for years to have their cases heard.

The backlog has decreased from the astonishing figure of 63,000 cases in June 2020. The long waiting times are attributed to a delay in processing visas and applications during the pandemic as well as a lack of resources.

In the annual report, AAT President David Thomas: "We are not sufficiently resourced to substantially reduce our significant on hand caseload."

“The number of cases on hand at the end of the reporting period continues to be an issue to be addressed.”

The refugee visa allows Ms Sanioura and her children to work, but it deprives them of other privileges that permanent residents and citizens enjoy.

"My daughter completed her studies at CIT in the hope that she would be able to study at university after that, but this is not possible because we cannot afford the international student fee."

She said her son and her other daughter were not able to study at the university level for the same reason.

Refugees and asylum seekers in Australia face significant obstacles in accessing higher education.

Due to the temporary nature of their visas, their only pathway to university is to gain admission as international students which could cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Just like Ms Sanioura, Khaled* and his family have been waiting for years for their case to be heard by the AAT.

A former diplomat, he moved to Australia in 2013 to represent Iraq, but the following years brought some unexpected developments.

Following a dispute with Iraqi officials that he attributes to sectarianism, Khaled was forced to quit his job.

Due to what he describes as "life-changing threats", he decided not to return to Iraq.

“I applied for a protection visa in 2017, but after six months my application was rejected.”

Khaled appealed the decision, but the tribunal has not yet heard his case.

He describes the delay in deciding immigration and refugee cases as "unfair”.

"This is time that passes from our lives and the lives of our children. What is our fault and what is the fault of our children?"

Like Ms Sanioura, Khaled feels bitter about his children not having access to higher education due to financial restraints.

"I feel so sorry for my children. I sacrificed everything for their safety and what happened was beyond my control."

Khaled said he has no alternatives to remaining in Australia.

I can't go anywhere. It's impossible for me to go back to Iraq. I lost my father in the Iran-Iraq war and I don't want my children to live the same bitter experience.

According to Ms Sanioura, her family is now stateless.

"The situation of the residents of Jerusalem is complicated as we have neither Palestinian nor Israeli documents. We are recognised by neither side.

“Our Jerusalem IDs have also expired because we’ve been away for more than two years."

Khaled ponders whether the Australian government would be willing to take responsibility for his safety as a former diplomat if he ever goes back to Iraq and face harm.

He says that there is what he describes as an "immediate threat to his life" if he returns to Iraq and that he cannot leave Australia for anywhere else.

"I feel imprisoned in Australia."

*Name has been changed for privacy reasons.