Highlights

- The Rosetta Stone was produced in 196BCE but only discovered in 1799 and has been a key translation device since then

- Scholars faced an uphill battle to get Egyptian studies incorporated into university curriculums in Australia

- Nowadays, Australian students can join multiple archaeological digs in Egypt

According to diplomatic interpreter and Professor of Linguistics, Dr Mohamed Gamal, arguably one of the world’s most treasured ancient artefacts, the Rosetta Stone, is on the face of it really nothing special after all.

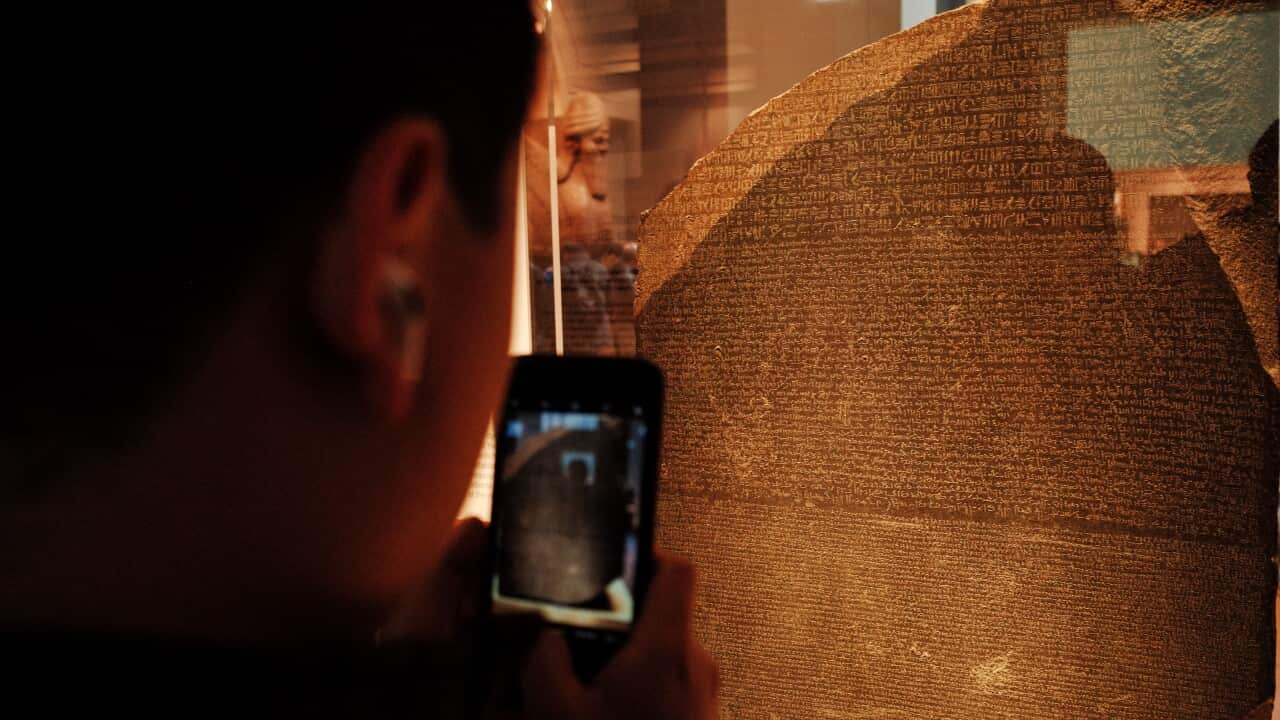

Accidentally discovered by Napoleonic soldiers in 1799 while digging the foundations for a fort extension, the stone, measuring 114cm x 72cm, is inscribed with 99 lines of text in three different languages – Hieroglyphic, Demotic (the everyday language of ancient Egyptians) and ancient Greek. Believed to have been produced in 196BCE, the stone, a chip off a much larger block represented a monumental breakthrough for archaeologists, allowing them for the first time to effectively “translate” hieroglyphs on countless other ancient Egyptian artefacts.

Believed to have been produced in 196BCE, the stone, a chip off a much larger block represented a monumental breakthrough for archaeologists, allowing them for the first time to effectively “translate” hieroglyphs on countless other ancient Egyptian artefacts.

Professor Naguib Kanawati pioneered Egyptology studies at Australian universities. Source: Naguib Kanawati/Macquarie University

Now, hundreds of years after the discovery of the stone, Dr Gamal says the stone is essentially an ancient “photocopy”, mass-produced for temples by canny Egyptian priests keen to keep their Greek rulers happy.

The Rosetta Stone is neither aesthetic, nor rare.

“Even the message on it is not unique in any way,” Dr Gamal said.

Dr Gamal was speaking on the 200th anniversary of the painstaking deciphering of the stone’s text, first attempted by English physicist Thomas Young (1773-1829).

“The real value of the stone does not lie in the stone itself, which, according to the inscriptions on it, had more than 40 identical copies spread across all of Egypt’s major temples,” Dr Gamal said.

It’s true according to the , which houses the Rosetta Stone as one of its most prized exhibits.

What does the stone "say"?

“The writing on the Stone is an official message, called a decree, about the king (, r. 204–181 BCE),” says the Museum’s website.

“The decree was copied on to large stone slabs called stelae which were put in every temple in Egypt.

“[The writing on the stone] says that the priests of a temple in (in Egypt) supported the king.

“The Rosetta Stone is one of these copies, so not particularly important in its own right.”

Dr Gamal said what made the Rosetta Stone incredibly special was that the message on it was written in the three languages common at the time.

Knowledge of how to read Hieroglyphic had all but disappeared by the 4th Century CE but by comparing the different types of writing, scholars were able to unravel the mystery of the ancient Egyptian script.

The stone would have lain undiscovered if it hadn’t been for Napoleon Bonaparte’s soldiers digging foundations for a kind of fort extension in 1799 in the Egyptian town of Rashid (Rosetta), a strategic port city 65km east of Alexandria.

Luckily, their officer in charge, Pierre-Francois Bouchard (1771-1822) immediately realised the importance of the find and the stone was spirited away for safekeeping.

Later, after Napoleon’s crushing defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the stone became the property of the British, but it took scholars another seven years to crack the code.

Deciphering the Rosetta Stone no easy task

Founder of the and The Rundle Foundation for Egyptian Archaeology, Professor Naguib Kanawati, credits French scholar Jean-François Champollion with comprehensively translating the stone’s inscriptions by 1822, therefore, marking a historical shift in how the world perceived ancient Egypt. “That is how scholars realised that hieroglyphs were actually alphabets. The carving of an owl did not refer to an owl, but it stood for the letter ‘m’ for example,” Prof Kanawati said.

“That is how scholars realised that hieroglyphs were actually alphabets. The carving of an owl did not refer to an owl, but it stood for the letter ‘m’ for example,” Prof Kanawati said.

The Rosetta Stone helped translate structures such as the Chapel of Khety. Source: supplied:The Australian Centre for Egyptology

“Deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs did not only enrich linguistics, but it also laid the foundations for establishing Egyptology as an academic discipline."

Dr Gamal said that until the stone’s discovery and deciphering, people had been baffled by the ancient Egyptian script for 14 centuries.

Ancient Egyptians, he said, were smart enough to appease their Greek Ptolemaic rulers.

The Ptolemaic dynasty ruled over ancient Egypt for 275 years, from 305BCE until the Roman conquest of the area in 30CE and began with Ptolemy, a bodyguard and general for Alexander the Great.

The inscription on the Rosetta Stone was one of several decrees passed by a council of priests that upheld the royal cult of the 13-year-old Ptolemy V on the first anniversary of his coronation.

The inscription reads: “He hath manifested the spirit of a beneficent god; and during his reign, having made careful inquiry, he hath restored the temples which were held in the greatest honour, as was right and in return for these things the gods and goddesses have given him victory, and power, and life, and strength, and health, and every beautiful thing of every kind whatsoever.”

Before the discovery, according to Dr Gamal, Egyptian hieroglyphs were perceived as magic signs used for curses and spells rather than the complex and intricate language it was later revealed to be.

“From here, came the obsession with and respect for the ancient Egyptian history and culture,” he said.

Prof Kanawati said the Hieroglyphic dictionary now consisted of six volumes.

Australian universities slow to introduce Egyptology studies

Yet, surprisingly, and despite this rich and endlessly fascinating history, it had taken around two centuries for Hieroglyphics to become a subject of interest for both the public and later, academic circles in Australia, he said.

As an example of this disinterest, Prof Kanawati said his early attempts to do a PhD in Egyptology at an Australian university had been met with laughter.

The head of a university archaeology department at the time had even described his drive to complete a doctorate on the subject as “illogical”, he said.

“You sound like an Australian student who wants to do Aboriginal studies in Egypt,” the Egyptian-born Egyptologist was told.

Undeterred and perhaps even spurred on by the resistance, Professor Kanawati went on to graduate with a PhD in Egyptology from an Australian university.

The answer is one word: persistence.

Neferrenpet and his wife offering to Amun at the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, Theban Tomb TT 147. Source: supplied:The Australian Centre for Egyptology

But as an academic, Prof Kanawati said he also had a duty to fulfill to the public beyond the walls of the university.

“I cannot just lock myself up in my office to do research. I have to reach out to people and help them learn about Egyptian history and culture,” he said.

“There is so much interest now in Australia in ancient Egypt. When the centre announces a lecture, the spots fill up in two hours.”

As a key driver of school curriculum planning, he said Australian students as young as year 7 can now learn about Egyptian history.

“Forty years ago, all the focus here in Australia was on the Greek and Roman civilisations. Apart from biblical studies, the Near East history was totally ignored,” he said.

Today, there were seven archaeological sites in Egypt run by Australian universities, he said.

Those sites include Macquarie University’s sites in Asyut and Dendera and Monash University’s site in the Dakhla Oasis.

“Students go there to do hands-on fieldwork,” Prof Kanawati said.

In the past, students might have been able to keep what they found in cases where identical copies of artefacts existed. However, these days, all discovered items were automatically the property of Egypt, which was the way it should be according to Prof Kanawati.

“We do not participate to get artefacts. We do it for the sake of learning and to produce more academic publications."