It had never occurred to me that the Turkish way of eating pasta — or makarna as we call it — was considered unusual until I saw the horrified reaction of a classmate who was over on a playdate.

"Ew, what have you put on this?" she asked as she picked up an offending spaghetti strand from the bowl I'd just proudly served her. "Where's the tomato sauce?"

Huh? Her questions left me as confused as she was. A tomato-based pasta sauce? What was she talking about? Why would anyone eat such a thing?

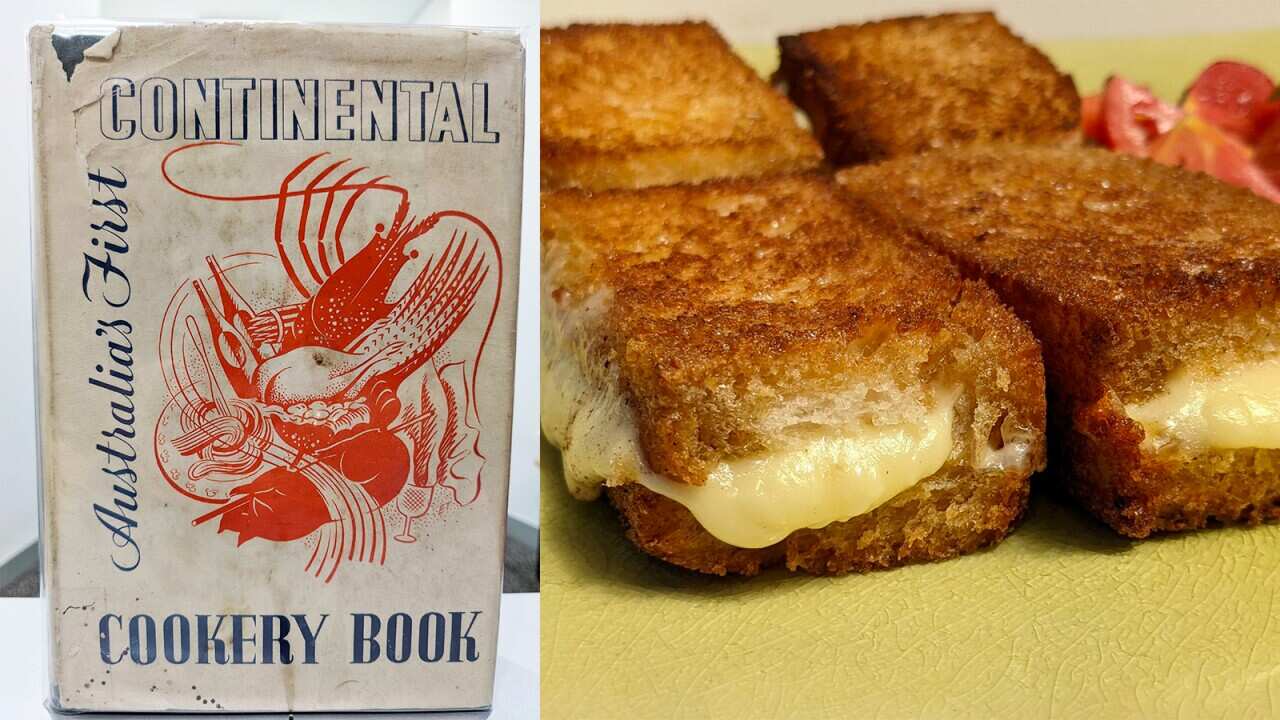

ITALIAN COOKING IN AUSTRALIA

The first book that taught Aussies to cook like Italians

To give this interaction some context, Turks tend to eat spaghetti (or any type of pasta really) that's been stirred with a thick paste of Greek-style yoghurt and often crushed garlic. Occasionally, instead of the garlic, we'll crumble some feta into the bowl or add mince (yes, even with the yoghurt), but that's pretty much it. Pre-internet, that's all I knew makarna to be. Then I backpacked my way through Italy and it was as much of a game-changer for me as it was for the locals I met along the way. Making my way through Venice, Florence, Rome, Luca and Pisa, I was shocked, then delighted, to discover a whole new world of pasta sauces. Rich ragu that had spent the better part of a day bubbling away on a stovetop, spaghetti aglio e olio and plenty of other mouth-watering toppings that didn't involve Greek-style yoghurt.

Making my way through Venice, Florence, Rome, Luca and Pisa, I was shocked, then delighted, to discover a whole new world of pasta sauces. Rich ragu that had spent the better part of a day bubbling away on a stovetop, spaghetti aglio e olio and plenty of other mouth-watering toppings that didn't involve Greek-style yoghurt.

Making my way through Venice, Florence, Rome, Luca and Pisa, I was shocked, then delighted, to discover a whole new world of pasta sauces. Source: Supplied

READ MORE

Spaghetti aglio e olio

I ate as much of the good stuff as my budget would allow, which, as an 18-year-old backpacker, wasn't much. However, more often than not, I would swing past a local supermarket, buy my three key ingredients and turn every hostel and convent kitchen I had the pleasure of enjoying into a Heston Blumenthal-style Turkish cooking class for the locals who watched on with a mixture of horror and fascination.

"You cannot put yoghurt on pasta!" I heard more than once as a panicked Italian came running in to stop me from creating what appeared to be the ultimate culinary sin. I soon learned "trust me" was not an adequate response and took to cooking a little extra each night to serve to those curious enough to try it.

A few refused to so much as pick up a fork, but word spread quickly about the strange Turkish-Australian cooking up some seriously unorthodox spaghetti and many tucked in, admitting that while it was unexpected, it was definitely tasty. "I can't believe I'm saying this, but it's wonderful," one young gentleman told me as he dove into a large bowl of the stuff. Another told me she was planning to make it for her family (I never found out whether she did or how it turned out). One fellow Italian traveller loved it but made me promise I wouldn't tell anyone ("It's the principle, you know?")

The dish connected me to others and now transports me to another time and place.

That summer, I took my makarna up and down the country, learning as much as I taught. At times my cooking — or perceived slaughtering of their national dish — inspired spirited discussion. Other times it provided moments of pure laughter. However, it always gave us, a traveller and the locals, the opportunity to get together. I made friends I never would have otherwise made and was taken out to local restaurants so I could experience 'real' spaghetti.

Now, some 25 years later, these experiences are not only some of my favourite memories of Italy, but they come to me whenever I make my makarna at home (at least once a week). Whether you agree with the sauce or not, the dish connected me to others and now transports me to another time and place.

Isn't that what all good food should do?

MORE FOOD STORIES FROM DILVIN YASA

Why a Turkish breakfast reconnects me with my ancestral homeland