What comforts can memories of food bring us? Phantom flavours have the ability to transport us to other times and places, but can they offer comfort amid the worst kind of misery and keep culture alive?

At the , in Darlinghurst, there is a handmade cookbook that is testament to how memories of beloved family dishes can sustain the spirit, if not the body. Located among other Holocaust artefacts in the concentration camps section of the museum, the slim book is no more than 15 cm x 10 cm; you could almost pass it over. The other artefacts it’s surrounded by – the brutality of camp uniforms; confiscated items such as combs and spectacles, toothbrushes and shoes; and patches with serial numbers – could swamp the hope that such a tiny object represents. But the cookbook is placed at the centre of a showcase, purposely drawing attention to something created, not taken away. This cookbook, known as the is a powerful statement about the way memory, food and survival are woven together in Jewish culture.

The other artefacts it’s surrounded by – the brutality of camp uniforms; confiscated items such as combs and spectacles, toothbrushes and shoes; and patches with serial numbers – could swamp the hope that such a tiny object represents. But the cookbook is placed at the centre of a showcase, purposely drawing attention to something created, not taken away. This cookbook, known as the is a powerful statement about the way memory, food and survival are woven together in Jewish culture.

It occurred to Edith to learn to cook from these women and collect their recipes because she had every intention of surviving. Source: Sydney Jewish Museum

The cookbook was made in 1945 by Hungarian-Jew Edith Peer (nee Gombos) when she was an inmate at Ravensbrück concentration camp for women, located in northern Germany. The cookbook is the only object of its kind in Australia and one of six known 'fantasy cookbooks' written by Holocaust concentration camp prisoners in the world. In 2015, it featured in a French documentary film, Imaginary Feasts.

Not knowing how to scramble an egg, she would sit with the other women during rare moments of spare time and listen to them “eat with words” as they shared their favourite recipes.

Barely an adult and not knowing how to scramble an egg, Peer would sit with the other women during rare moments of spare time and listen to them “eat with words” as they shared their favourite recipes. It occurred to Edith to learn to cook from these women and collect their recipes because she had every intention of surviving.

Peer, was put to work in an office of the Siemens & Halske electronics company and so was able to steal paper and a pencil. "The paper was torn into even-sized sheets and, with the help of a friend, she wired it together, like a staple," says Roslyn Sugarman, Head Curator at the Sydney Jewish Museum.

Using the stolen paper and pencil, her fellow inmates recalled family dishes that were rich and heavy, meant to fill the belly: goulash, potato dumplings, stuffed cabbage, paprika fish and desserts. So many desserts. Desserts for observance, desserts to celebrate, desserts to indulge, such as nougat cream, (Austrian chocolate cake) and (a shredded pancake). "If you think of a house filled with the smell of baking, that's the smell of home," says Sugarman. More than half of the 97 recipes (written in Hungarian and German) in the cookbook are for cakes and trifles, biscuits and creams. In many of the recipes, there are no measurements or weights for the ingredients. In the notes she wrote in 1996, when she donated the cookbook to the museum, Peer said these recipes were written by women who had never used a kitchen scale or cookbook. "They simply knew how to cook," she said.

In many of the recipes, there are no measurements or weights for the ingredients. In the notes she wrote in 1996, when she donated the cookbook to the museum, Peer said these recipes were written by women who had never used a kitchen scale or cookbook. "They simply knew how to cook," she said.

"Women fought for their survival under the most inhuman circumstances by using the only positive approach available - fantasy cooking.” Source: Sydney Jewish Museum

Sugarman tells SBS how “the phenomenon of talking about food in the concentration camps of Europe was commonplace because the inmates were continuously starving with food rations calculated to starve them.” Talk of food was not only a way of comforting each other, though. "This tiny little book is an act of resistance to maintain a sense of hope and humanity," says Sugarman.

When Peer donated her book to the museum, she described its significance as evidence of “how women fought for their survival under the most inhuman circumstances by using the only positive approach available - fantasy cooking”.

Memory is long in Jewish culture, it is an ingredient in recipes that are passed from one generation to the next.

The prisoners in Ravensbrück were from all over Europe and there were many that weren't Jewish. "They didn't all have a common ethnic or even religious identity but they were all women so they were most likely cooks," says Sugarman. "They all spoke different languages and might not even be able to communicate with one another but they were united by circumstances and food was one commonality."

She says writing down the recipes reminded them of home, of family and shared meals. It was an act of memory, of passing down a recipe from a mother or grandmother, and also gave them hope for a future in which they could again create lavish meals.

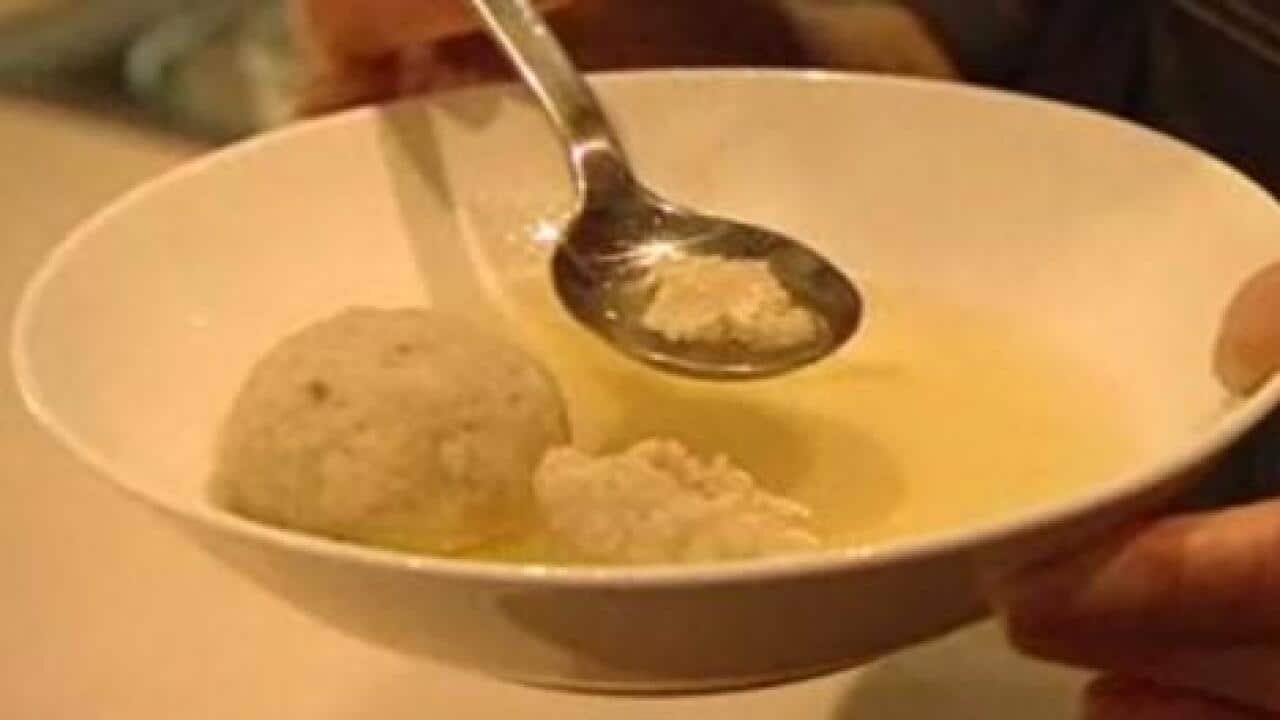

"Most cultures gather around the table; it's not exclusive to Jews. But Jews have a special relationship with food because there are so many rituals around the preparation and eating of food, for instance on shabbat (the Jewish sabbath) and on Rosh Hashanah (Jewish new year)," says Sugarman. Peer along with many other Holocaust survivors made their way to Australia after the war, the influx of which built the foundations for this nation’s rich Jewish community. The , the Sydney-based group of friends who have been sharing recipes from the Jewish community since 2006, honour grief and survival with their special blend of cooking and storytelling. The much-loved sorority tells SBS that “people who have been uprooted or displaced or who have lost their families, their homes and their heritage, will often search for something remaining of the life they once lived. This may be a dish that they remember fondly – their mother’s poppyseed strudel, their aunt’s almond bread or their nana’s chicken soup and kreplach.”

Peer along with many other Holocaust survivors made their way to Australia after the war, the influx of which built the foundations for this nation’s rich Jewish community. The , the Sydney-based group of friends who have been sharing recipes from the Jewish community since 2006, honour grief and survival with their special blend of cooking and storytelling. The much-loved sorority tells SBS that “people who have been uprooted or displaced or who have lost their families, their homes and their heritage, will often search for something remaining of the life they once lived. This may be a dish that they remember fondly – their mother’s poppyseed strudel, their aunt’s almond bread or their nana’s chicken soup and kreplach.”

Using the stolen paper and pencil, her fellow inmates recalled family dishes that were rich and heavy, meant to fill the belly. Source: Sydney Jewish Muesum

These are the kind of recipes found in the Monday Morning Cooking Club’s cookbooks along with stories from survivors about worlds left behind and new lives made. The MMCC explains how survivors came to Australia with only the memory of childhood dishes, how their efforts to recreate them helped a community heal and lay foundations for a new home.

In every dish that is cooked, there is a story of what has been lost and what has been saved. Memory is long in Jewish culture, it is an ingredient in recipes that are passed from one generation to the next. This sense of tradition is what compelled the women of Ravensbrück to write down their recipes in the most desperate conditions - imprisoned yet determined to cook, if only in fantasy, without a pot or knife, as an act of hope. Remembering is a way to honour the past but also secure a future.

Peer survived and immigrated to Sydney in 1951. She died in 2003. "Edith understood the significance of what she had created," Sugarman says. "She said the reason she wanted the book to be on a shelf in a home was not for the recipes, but so that people would remember there were women who suffered and who had the resilience to survive."