When I ask Emily and DJ Lee (the owners of Perth café and unofficial bánh mì king and queen of the city) what chè is, their answer is simple: “It’s a little bowl of happiness.”

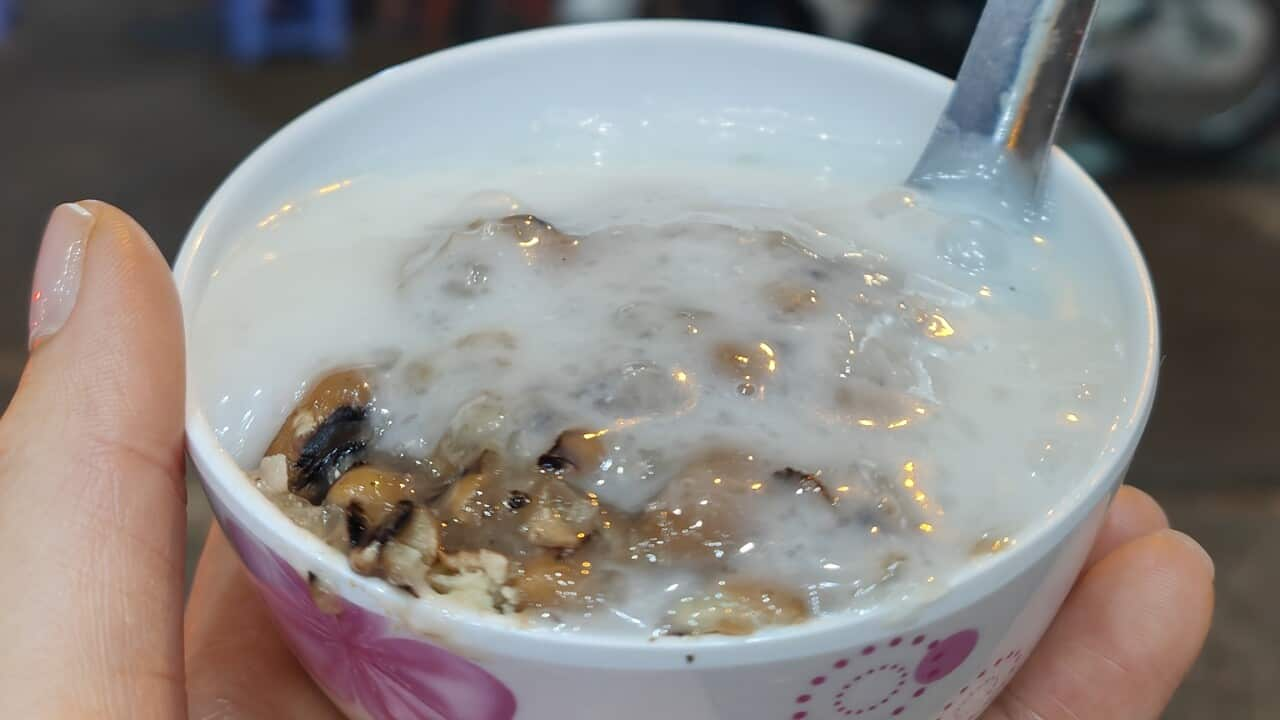

A smile stretches across my face, taking me back to a flimsy plastic stool at Mrs Diep Che Dessert on the corner of District 5 in Hồ Chí Minh. Sitting centimetres from the floor on a plastic stool, I’m clutching a palm-sized bowl. It’s a murky white, with black eyed peas peeking along the edges.

My enthusiasm for dessert means I’ve got another dish right beside me – my second dessert – in which the yellow end of a banana emerges like an island from a pool of sago. I close my eyes against the rev of motorcycle engines, the chatter of families stumbling past and take a scoop.

Chè. It’s a beautiful catch-all for some of the best Vietnamese desserts. It’s a dessert drink, soup and pudding all in one, not dissimilar to the Filipino dessert “halo-halo”.

Credit: Supplied

What does chè taste like?

Chè can be eaten warm or cold. It’s a symphony of textures - the soft chew of glutinous rice, bouncy sago suspended over a smooth yellow custard and the jamminess of slow cooked beans.

Even though there are numerous wonderfully colourful iterations, fundamentally chè is a simple concoction – it is always soupy, milky, not too sweet, and has a burst of more-ish savouriness thanks to the assortment of toppings.

In Vietnam, at the countless chè stalls lining the streets, the conductor orchestrating this symphony is typically sitting behind an array of cauldrons, moving their hands to the rhythm of customer’s orders being shouted at them.

Credit: Ange Yang

Lee’s words ring true as I travel up and down the coast of the beautiful peninsula. At Chè Hẻm in the historical capital Huế, I devour a version dotted with bright yellow lotus seeds which I crush with my teeth. In Hanoi, cola dark grass green jelly wobbles in a bowl of white coconut cream, dotted with corn, yellow and crushed peanuts. My favourite though is chè chuối – a blue-grey bowl of sago with crushed peanut (also the most popular ones at Mrs Diep Che Dessert).

No matter where I am, I’m always sitting on plastic stools, inches from the ground, knees brushing up against strangers digging into their bowls of chè. I learn how beans can bring people together, how our shared love of chè breaks across the language barrier, leaving us mixing our bowls with laughter to the beats of two languages and the tapping of fingers on screens as we reach for Google Translate.

Finding comfort and community in a bowl

The Lees understand this sense of community that chè brings. “When we have family gatherings at least one or two family members will bring a sweet dessert and it is often chè and fruits. So during dinner we eat together, then after dinner we clean up, then we let the food settle down before we gather at the table again and have a bowl (or three!) of chè each.”

The Lees share the chè community spirit every summer at their café too.

Our shared love of chè breaks across the language barrier.

For Tran, the attention and care put into the chè ba màu at Hoang Gia Quan in Adelaide is where she finds comfort. “The owner, I know her as Cô Yến, is a stickler for quality and freshness - she makes every component herself (I think she even makes the coconut milk from scratch) and doesn't serve it unless she's happy with everything. I think that attention to detail goes a long way, and I appreciate the hard work and passion that goes into making it.”

For me? Chè isn't the first bean dessert I’ve found comfort in – that honour lies with the Malaysian desserts I grew up with, like the red beans at the heart of a mountain of ais kachang. But chè has rocketed up the pantheon of my dessert lists, clearly the captain of my campaign pitch that beans belong in dessert.